In 1988, New York City opened the Rose M. Singer Center, a new, state-of-the-art women’s jail on Rikers Island named after the women’s-rights advocate and criminal-justice reformer who championed its founding. The approach to corrections at “Rosie’s” was meant to be rehabilitative and therapeutic, rather than cruel and punitive. The buildings had skylights and the walls were painted in friendly colors. The facility was equipped with a nursery where women who had recently given birth could stay with their infants while awaiting trial. A large courtyard where detainees could freely meander within a protected perimeter was planted with trees and flowers. Job training was offered in horticulture and the culinary arts, and a restaurant was built on site where women could practice their new skills. At the facility’s ribbon-cutting ceremony, Mrs. Singer said, “I hope that the center will be a place of hope and renewal for all the women who come here.”

Women’s jails and prisons in the U.S. have long been compelling targets for feminist intervention. “A place of hope and renewal” is not how one generally describes a jail, and yet an effort to frame correctional facilities for women as sites of protection rather than unfreedom has been under way since the founding of the first such institutions in the country. In part, this is because each new prison is conceptualized in reaction to the failures of the ones before it; the first women’s prisons were championed by activists who were appalled by the dangerous circumstances of women held in mixed-gender facilities. For some advocates, it is tempting to believe that a given facility’s violence and chaos are site-specific, inspiring optimism that a new building, or new leadership, might yield different outcomes. This is the essential tension between abolitionists who believe that “cruel and unusual” is a feature, not a bug, of incarceration and reformers who believe that conditions of confinement can be iterated in the interest of justice and human rights.

The oldest women-only, state-run prison in the U.S., the Indiana Reformatory Institute for Women and Girls, opened in 1873. Its primary founders, Sarah Smith and Rhoda Coffin, were both Quakers who became nationally recognized prison reformers and women’s-rights advocates. Until Smith and Coffin’s campaign, state prisons had been managed and overseen almost exclusively by men; the reformers argued that an all-female facility should be run by women, who would be uniquely suited to meet the needs of incarcerated women. Smith became the reformatory’s first superintendent, or warden, and was lauded for her progressive, humane institutional leadership during her tenure. Her portrait still hangs in the hall of the reformatory’s current incarnation, the Indiana Women’s Prison (I.W.P.).

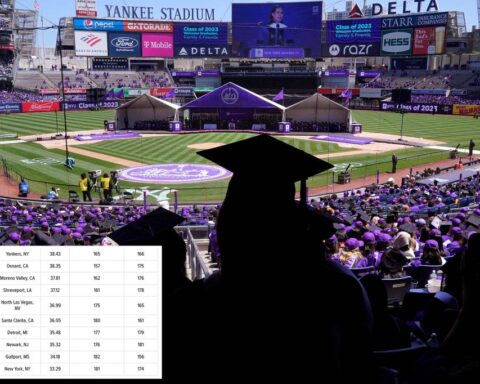

In 2013, a group of incarcerated women at I.W.P. met with Kelsey Kauffman, a local academic. The prison had previously offered a comprehensive college program in the nineteen-nineties and two-thousands, but the Indiana state legislature had cut off the program’s funding in 2011. At the time of the 2013 meeting, Kauffman was running ad-hoc college courses at the prison, relying on only volunteers and donations. She had struggled to find materials with which her students could be trained to learn research methods; they did not have direct access to the Internet or to a public library, and interlibrary loans to the prison were slow and cumbersome. Kauffman did have, however, an archive of documents pertaining to the prison’s founding and history, and her idea was to use these primary sources as grist for the research mill. She proposed to her students that they spend a few months conducting a historical investigation of the institution that confined them, and that, at the end of the course, they produce a pamphlet about the prison that could be shared with visitors interested in its origins.

That group became the foundation of the Indiana Women’s Prison History Project, a collective of incarcerated and now formerly incarcerated women who have, over the past decade, produced an astonishing body of investigations into the early history of Indiana’s correctional system. This year, the New Press published an anthology titled “Who Would Believe a Prisoner?: Indiana Women’s Carceral Institutions, 1848-1920,” with contributions by twenty-nine members of the collective.

The book is a collection of essays, academic chapters, and one original play that reflect not only the authors’ extraordinary feat of having produced original scholarship while incarcerated but also what Kauffman calls the authors’ “epistemic privilege”—the particular benefit of lived experience which positions them in conversation and continuity with the subject of their inquiry. “We offer a new terminology: the embodied observer, one who views the archive from the position of the captive, from the inside of their experience,” writes Michelle Daniel Jones, in her introductory chapter to the book. The embodied observer, in this case, is predisposed to believe the accounts of incarcerated women over the accounts of her jailers when those narratives are in conflict. The observer is also alert to what unflattering or incriminating stories may be absent from the archives.

Early in their studies, Kauffman’s students proved able to scrutinize source material not only for what it revealed but also for what it omitted; to detect which voices were suppressed in an official record. The collective’s narrative is a more thorough, more critical, and more painful history than the one previously told about the first state-run women’s prison. “Who Would Believe a Prisoner?” emphasizes the available testimony of incarcerated women and girls who spoke out against Sarah Smith’s cruelty toward them. This included the regular use of “ducking,” the practice of submerging girls’ faces under cold, running water for long periods of time as a punishment for a myriad of small infractions, such as suspected masturbation. The book also reveals compelling evidence that the prison’s first doctor, a celebrated gynecologist, was likely abusing his patients and practicing surgeries and procedures on them to further his career. Perhaps most critically, it also presents the reformatory in context, not as the pioneer women’s detention center in nineteenth-century Indiana but as only one part of an institutional ecosystem that conspired to confine women in the state.

While combing through the registries from the reformatory’s early years, Jones, now a history graduate student at New York University and one of the book’s co-authors and editors, noticed that none of the women listed were convicted of crimes related to prostitution. She and her colleagues knew prostitution was outlawed in Indiana and considered a scourge of respectable society; they could not believe that sex workers were not being arrested and imprisoned; and yet none appeared to be at the state’s only official women’s facility. “Where were the hos?” Kauffman recounts Jones asking at the beginning of every class.

Jones and her colleagues returned to this question week after week without finding satisfactory explanations. With the assistance of a librarian outside the prison, they finally discovered that the reformatory’s reputation as the first women-only correctional facility in the country was unearned: an order of nuns called the Sisters of the Good Shepherd had, for decades, been running a parallel set of institutions throughout the country to incarcerate women accused of sex crimes. Some women were sent to these homes at the behest of the state after criminal conviction; others were involuntarily committed at the request of their families or neighbors for “safe keeping.” Girls who had been taken as wards of the state in proto-family court proceedings were also committed to the nuns’ guardianship. One of these institutions, the House of the Good Shepherd in Indianapolis (H.G.S.), was operational months before the reformatory’s opening.

The anthology’s authors compare H.G.S. and its sister houses throughout the U.S. to the deadly Magdalene Laundries of Ireland, a similar network of convent-run homes for “fallen” women, and to private prisons. In the authors’ estimation, the contrast between the reformatory, owned and operated by the state, and H.G.S., owned and operated by the church, is a distinction without a difference. “If a prison is defined as a place of confinement for crimes and of forcible restraint, and if the persons committed to these places cannot leave when they want to . . . . It becomes irrelevant whether the place is called a prison—or, instead, a refuge, correctional facility, house, penitentiary or even laundry,” Jones and a colleague named Lori Record write in a paper about H.G.S. Their analysis stresses the trauma suffered by women incarcerated in both types of institutions, the hypocrisy of the overseers, and the continuity between the punishment culture of the late eighteen-hundreds and their own experiences as incarcerated women in the twenty-first century.